‘You wouldn’t think such a violent place to be kind of pretty’: When Billy Connolly came to Ireland during the Troubles

The long-lost documentary Big Banana Feet charts the Glasgow comedian’s visit in 1975 to perform shows in Belfast and Dublin

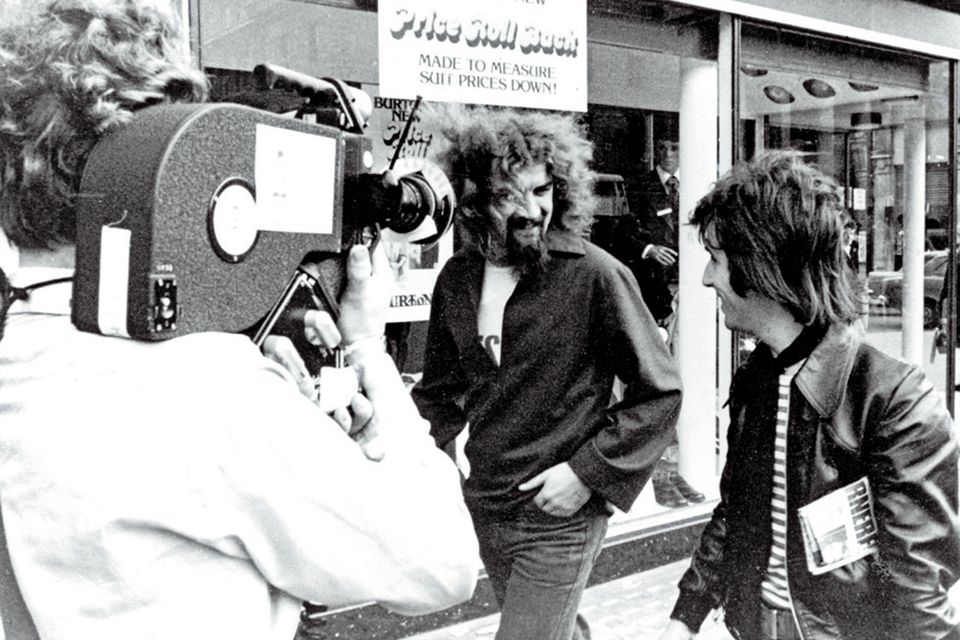

Billy Connolly being filmed during his 1975 tour

In October of 1975, at the end of a long tour of Britain, Billy Connolly came to Ireland to perform his comedy act here for the first time. The Troubles were at their height, and he had been warned by many that his safety could not be guaranteed. “They asked me,” he tells a journalist at a Dublin press conference, “so I thought what the hell.”

He brought with him a film crew, and cameraman David Peat was so omnipresent that Connolly stopped noticing him. The resulting documentary offered an intimate insight into a comedian who at that point was still honing his act: it’s also a fascinating snapshot of a very different island, north and south. Directed by Murray Grigor and Paddy Higson, Big Banana Feet was given a limited cinema release in the UK, then the distributor went bust, and the film went missing.

It was presumed lost forever until British Film Institute archivist Douglas Weir tracked down a 16mm copy of the film and bought it for £50. He has restored it and reinserted two risqué jokes censored from the original cut. Cinemagoers will get a chance to see the film from May 10, and a DVD release is also imminent.

Trailer for Big Banana Feet (1976) starring Billy Connolly

Born in Dover Street, Glasgow to parents of Irish extraction, Billy endured a hard childhood in the city’s tenements which he would later mine to great comedic effect. His mother left home when he was four, and his father beat and sometimes sexually abused him. His Catholic school was equally violent, but when he was seven or eight, Connolly discovered an innate talent for making people laugh. His real passion though, was music.

After working as a welder in the city’s shipyards, he began performing on the UK folk circuit in the late 1960s, crossing paths with the likes of Christy Moore and Gerry Rafferty. But by the early 70s, he began to notice that his little between-song monologues were attracting more attention than his music. A legendary stand-up comedian was born.

When he landed in Dublin on October 20, 1975, however, Billy was still calling himself a “banjo player” and “a comic singer”. Several of his comic songs had become chart hits in the UK, and onstage he still hid behind his guitars and banjos: he wasn’t quite confident enough to stand on his own and just tell stories. In Big Banana Feet, though, we get glimpses of the brilliant comic he would shortly become.

Connolly would later embrace his Irish heritage, and locate a cottage lived in by his ancestors before the Famine, but in Big Banana Feet, Ireland feels very unfamiliar. “It’s totally foreign to me,” he tells his manager, and visibly wilts in the glare of the Dublin media spotlight.

Read more

RTÉ’s Áine O’Connor helpfully warns him that he might get blown up in the north, and reminds him of the recent killing of the Miami Showband by the UVF. Fr Brian D’Arcy quizzes him on religious jokes, Rodney Rice inveigles him into doing a radio interview, and a young and hirsute Niall Stokes asks him if his act is based on working-class Glasgow humour. “I should imagine so, being a working-class Glaswegian,” Billy answers testily. “These receptions get very wearing,” he says afterwards.

He stays in a suite at the Gresham (“this’ll do me!”), and wanders down O’Connell Street with his retinue in search of a pub. He smokes constantly: so does everyone. And he is highly amused that every second person he meets appears to bear the surname Connolly.

It’s the end of a long and gruelling tour, and Billy is clearly exhausted: but he comes to life whenever he takes to the stage, and feeds off the audience’s rowdy energy.

His comic songs go down a bomb, and he was a very accomplished banjo player. Some of his routines and references are necessarily dated, but as soon as he talks about his childhood, or the nocturnal habits of working-class Glaswegians, Billy’s comedy comes into its own.

During a skit about a drunk person trying to eat chips, he refers to Drumchapel, where he spent his teens, as “a reservation on the outskirts of Glasgow”. As he talks, Billy is still learning to accumulate humour during a story, and become that rarest of things — a comedian that can leave an audience helpless with laughter. “I’m a Partick Thistle fan,” he tells the Dublin crowd, “we’ll get into Europe next year, if there’s a war.”

He’s very good with hecklers. “Gis a shout when you’re finished pal,” he tells a Belfast rambler, “and I’ll get on with it.” And when someone at the Dublin gig shouts out, for no apparent reason, the letters ‘IRA’, Connolly’s response is withering. “That’s really brave — I’d love to see you doing that at Ibrox.”

On the plane up to Belfast, he hums the theme music from Dambusters, and amuses the crew with a half-decent impression of Ian Paisley. “I’ve only one thing to say to you Mr Connolly — this is not Sodom, or Gomorrah!” As they come in to land he stares out the window and says “you wouldn’t think such a violent place to be kind of pretty”.

On the ground, soldiers are everywhere. He chats with Scottish members of the 15th Parachute Battalion, and jokingly asks them how the hell they got there. There are soldiers at the gig as well, jostling around him as he makes his way onstage. Security is a constant concern, and you can see that he’s nervous, but once onstage he connects with his audience immediately.

“It really is nice to be in Belfast,” he says, then emits a hollow laugh. The crowd love it, and laugh even louder when he pretends a flower thrown at him is a bomb.

Though Billy had been raised in a deeply sectarian city where even sporting allegiances were decided on the basis of faith, his understanding of the northern conflict was as sketchy as many British person’s, an ignorance he was keenly aware of. He tells a journalist afterwards that he had prepared some “orange-green” bits but has decided against doing them, reckoning that Belfast people probably wanted “a break from all that”. He got the tone just right, and the Belfast crowd loved him.

In Dublin, several people mentioned having seen Billy on the TV show Parkinson. Those early conversations with the chat-show host raised Connolly’s profile hugely, and also taught him a lot about what worked comedically, and what didn’t. Within a couple of years, the guitars were sidelined, and Billy grew ever more ambitious in terms of the darkness and complexity of his themes. And he became one of the greatest stand-ups the world has ever seen.

As he left Belfast, and Ireland, he was buoyed by the connections he had made. “I’ll be back,” he said, “I’ll tell you that.” It was the beginning of a mutual love affair between Billy Connolly and Ireland that has never really ended.

Join the Irish Independent WhatsApp channel

Stay up to date with all the latest news