Llamasoft – The Jeff Minter Story review: Inside the mad mind of a gaming pioneer

Platforms: PS (tested), Xbox, Switch, PCAge: 16+Rating: ★★★★☆

The theatre world recognises the works of Harold Pinter as being so distinctive they’ve spawned their own adjective: Pinteresque. In gaming, cult creator Jeff Minter surely deserves a similar accolade for his idiosyncratic oeuvre that began in the early 1980s on primitive home computers and continues to this day on modern consoles.

Frankly, game history specialist Digital Eclipse – now a part of Atari – missed a trick by not calling this interactive documentary Minteresque. In fairness, the Llamasoft brand used by Minter is probably just as recognisable for gamers of a certain age.

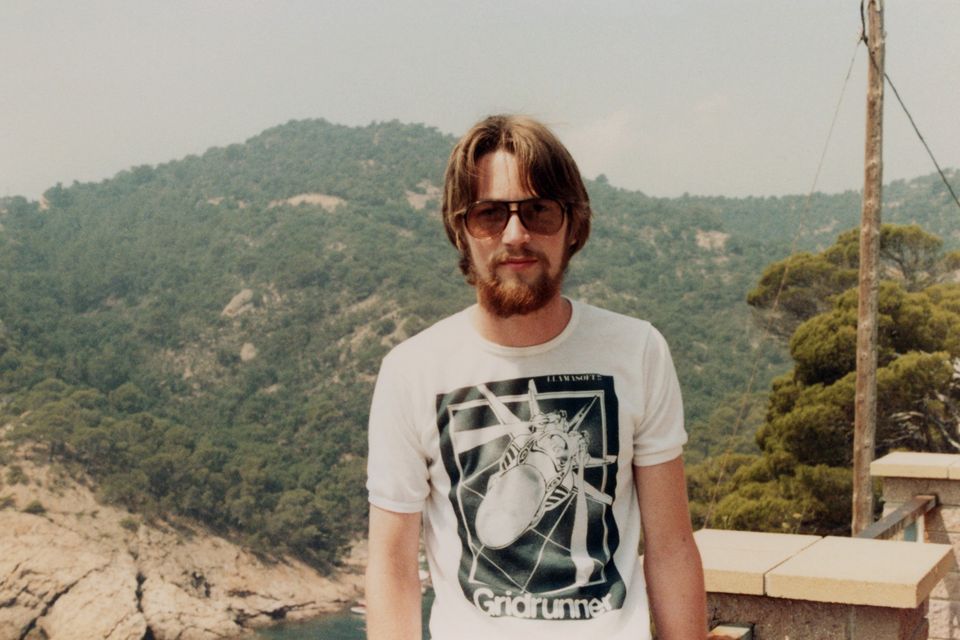

The eccentric 61-year-old Englishman made a name for himself in the 80s with his style of likeably bizarre arcade shooters defined by abstract graphics and extreme difficulty – though the latter was always undercut by silly humour and an obsession with, yes, llamas. Like many of the era, his was a one-man show – designer, artist and coder – while also self-marketing and distributing his games with the help of his parents.

His shaggy appearance, dislike of greedy big businesses and carefree attitude endeared him to players attracted to his prolific output of simple but singular Llamasoft titles such as Attack of the Mutant Camels and Gridrunner.

Digital Eclipse approaches this deep dive into Minter’s back story in the same way it treated its two earlier projects that focused on the early days of Atari and Prince of Persia creator Jordan Mechner. Minter’s chronicle is arranged in four chapters on a clickable timeline, incorporating photos, screenshots, notes from his archives and video interviews. It touches on his catalogue of more than 60 games – and makes more than 40 available in playable form.

You might flick from a photo of him at an early computer trade show in Birmingham to a handwritten coding note to a reproduction of his long-running printed newsletter where he told fans at length what he was working on or playing. Every chapter is dotted with video clips of contributors describing his influence or Minter himself reflecting on his thought processes at that time.

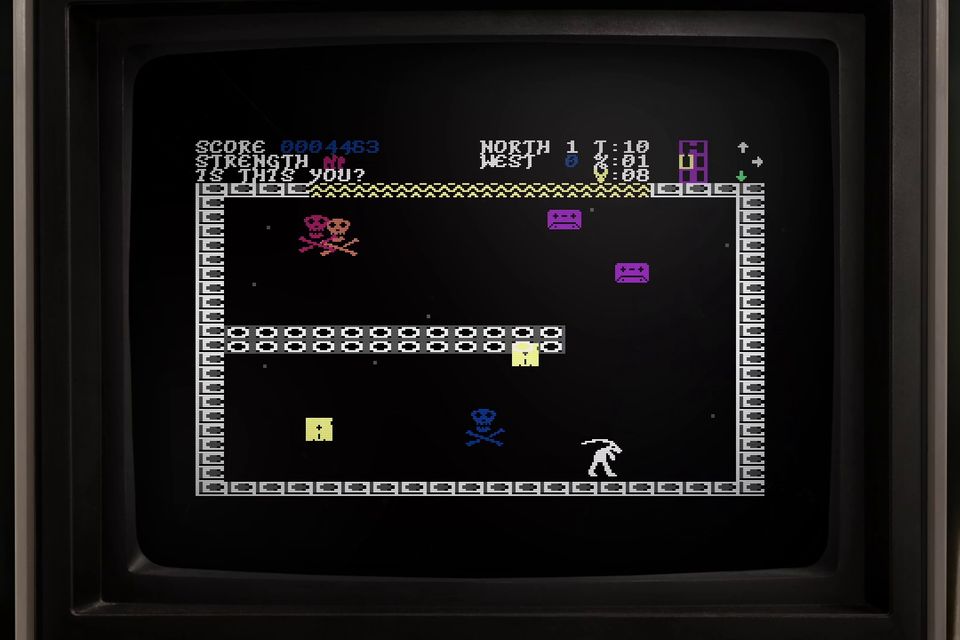

It's fascinating in a nerdy way, probably of most interest to the generation who fondly remember the games. Certainly, anyone unfamiliar with his work, or of less advanced years, might blanche at the quirky but unforgiving and one-dimensional titles of early Llamasoft, many of which were riffs on other people’s games.

But Minter was anything but one-dimensional himself. In 1984, he began experimenting with “light synths”, abstract visualisers tied to music or cursor movement. His 1990s career brought us Tempest 2000 and a host of games built around a rave aesthetic of pulsing visuals and thumping tunes. These more than anything could be labelled Minteresque for their sensory overload.

Unfortunately, perhaps for licensing reasons, the Digital Eclipse documentary does not incorporate playable versions of later classics such as Space Giraffe and Polybius. Given that the second half of Minter’s catalogue is by far the more palatable to a 2024 audience, it leaves a noticeable gap in the Llamasoft story.

Still, anyone who spends a few hours digitally in Minter’s company couldn’t fail to warm to this talented eccentric and his prodigious body of work. You might not play most of the 43 games here more than once but a handful will pull you back in time after time, if only to marvel at the mad mind of Minter.

Join the Irish Independent WhatsApp channel

Stay up to date with all the latest news